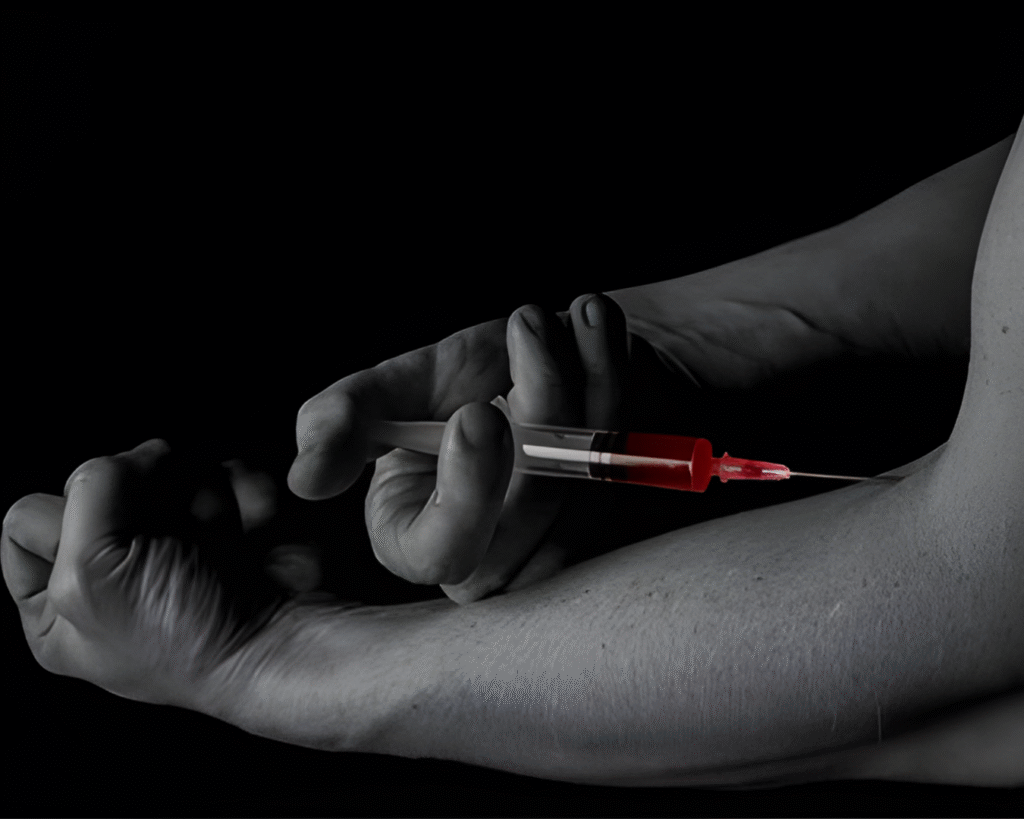

Bluetoothing, also known as flashblood, has emerged as one of the most alarming high-risk drug practices observed in the world today. It involves a person who has just injected a drug, drawing their own blood into a syringe and transferring it to another person who then injects it. This desperate act is often driven by withdrawal, scarcity, or poverty. Recent reporting has revealed that this practice is not only real but growing, especially in communities already struggling with drug dependency, unemployment, and limited access to healthcare.

Investigations by national media outlets highlight how bluetoothing has taken root in neighbourhoods facing economic hardship. Journalists describe the practice as a “ticking time bomb” for HIV and hepatitis transmission and a stark reflection of the vulnerabilities in many Nigerian communities. Health experts quoted in these reports warn that the amount of drug present in shared blood is negligible, yet the risk of infection is extremely high.

The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) estimates that 14.3 million Nigerians aged 15 to 64 currently use psychoactive substances. This enormous population of drug users creates an environment where dangerous coping strategies such as bluetoothing may spread if not urgently addressed.

Why People Engage in Bluetoothing

Those who engage in bluetoothing rarely do so willingly. The practice emerges in situations where individuals experience severe withdrawal, cannot afford another dose, or have been misled into believing that shared blood will provide relief. In many affected communities, stigma prevents people from seeking help, and misinformation fills the gap left by inadequate public-health education.

Bluetoothing carries life-threatening risks. Injecting another person’s blood dramatically increases the likelihood of contracting HIV, hepatitis B and C, and serious bacterial infections such as sepsis. Because syringes are often reused, the danger multiplies even further. Health workers describe the practice as one of the most efficient ways of transmitting blood-borne diseases.

The emergence of this harmful trend in Nigeria signals deeper underlying issues. Factors such as poverty, unemployment, homelessness, trauma, and limited access to mental-health services all contribute to environments where such desperate actions occur. Reports also indicate that young people are particularly vulnerable due to peer pressure, social exclusion and the rising availability of cheap, harmful substances.

Parents, caregivers and community leaders have critical roles to play. Recognising early signs of substance dependency, offering non-judgemental support and promoting open conversations can help protect young people from falling into harmful practices. Compassionate engagement is far more effective than punishment. It encourages help-seeking behaviour and reduces the likelihood of secretive or unsafe drug use.

Experts emphasise that criminalisation alone cannot solve the problem. Instead, Nigeria must strengthen its public-health response. This includes improving access to harm-reduction programmes, expanding treatment and rehabilitation services and supporting community-based outreach. Health organisations consistently stress that life-saving interventions such as clean needles, counselling and HIV testing reduce harm and help people regain stability.

Key Steps for a Stronger Response

- Expanding community outreach and peer education

- Strengthening access to evidence-based treatment and rehabilitation

- Providing HIV testing, counselling and clean-needle services

- Increasing public-health education that promotes understanding rather than stigma

Bluetoothing is more than a dangerous drug trend. It is a warning sign of deeper social and public health challenges that require urgent attention. By recognising its drivers and responding with compassion, accurate information and evidence-based interventions, communities can protect vulnerable individuals and prevent this harmful practice from spreading.

The time to act is now, before another young person picks up a needle not to inject a drug, but to share someone else’s high and unknowingly injects their death sentence. Because in the story of bluetoothing, what’s truly being transmitted isn’t just blood. It is a cry for help that Nigeria cannot afford to ignore.